Pairs and pair structures

- Summary

- As you should know by now,

consis one of the core Scheme procedures. Most typically,consis applied to two arguments, a value and a list, and we think of it as prepending the value to the front of the list. You also know from experimentation thatconscan not take fewer than two arguments nor more than two arguments. You have also found thatconscan still be called with a non-list as the second argument, and in this case the thing built has a strange dot before that element. In this reading, we consider what is happening behind the scenes when you callcons. We also useconsto build structures other than lists.

Detour: Symbols

Before we explore pairs, we’ll take a quick detour to remind you of one of Scheme’s other key data types, the symbol. Symbols look a lot like words (and perhaps even strings), except that they don’t have quotation marks around them. Internally, Scheme uses symbols for all of the names that you write in your program. Many Scheme programmers find them useful when they just need a simple, readable, value to pass around.

You write symbols with a single quote mark (', which we also call

a “tick mark”) and the word you want to serve as a symbol. For

example, 'aardvark is a symbol that corresponds to the word

“aardvark” and 'zebra is a symbol that corresponds to the word

“zebra”.

When some versions of Scheme print out symbols, they do not give you the single quote symbol. Fortunately, DrRacket is a bit nicer.

> (quote aardvark)

'aardvark

> (list (quote aardvark) (quote zebra))

'(aardvark zebra)

> aardvark

reference to undefined identifier: aardvark

Symbols are atomic. Unlike strings (which symbols seem to resemble),

symbols do not support procedures, like string-ref or substring,

that extract some part of the symbol.

Hence, there are only a few procedures applicable to symbols:

symbol? checks whether a value is a symbol and both eq? and equal?

can be used to compare symbols.

Why would we use symbols, if those are the only available procedures? Because they’re simple and sometimes a bit more fun than numbers. Why do we remind you of them now? Because they’re also nice to use in diagrams, and we have a lot of diagrams in this reading.

Box-and-pointer diagrams

As we have seen, Scheme uses cons to build lists.

As you may recall, cons takes two arguments.

Up to this point, we’ve expected that the first element has been a value and the second has been a list.

When you call cons, Scheme (Racket, DrRacket, something like that) builds a structure in memory with two parts, one of which refers to the first argument to cons and the other of which refers to the second.

This structure is called a “cons cell” or a “pair”.

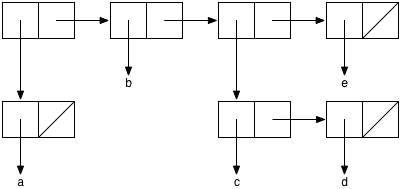

Let us now consider a graphical way to represent the result of a call to cons.

The basic idea is to use a rectangle, divided in half,

to represent the result of the cons. From the first half of the

rectangle, we draw an arrow to the first element of a list, its car;

from the second half of the rectangle, we draw an arrow to the rest

of the list, its cdr. When the cdr is null (the empty list), we draw a

diagonal line through the right half of the rectangle to indicate that

the list stops at that point.

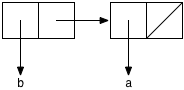

For instance, the value of the expression (cons 'a null) would be

represented in this notation as follows:

Since the value of the expression (cons 'a null) is the list '(a),

this diagram represents '(a) as well.

Now consider the value of the expression (cons 'b (cons 'a null)),

or in other words, the list (b a). Here, we draw another rectangle,

where the head points to b and the tail points to the representation of

(a) that we already have seen. The result is:

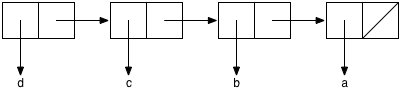

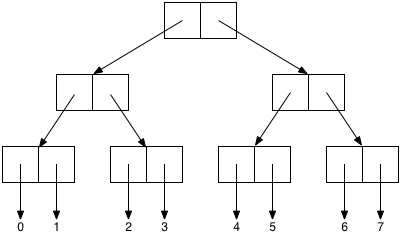

Similarly, the list '(d c b a) is the value of the expression (cons

'd (cons 'c (cons 'b (cons 'a null)))) and would be drawn as follows:

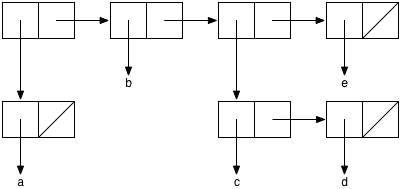

A similar approach may be used for lists that have other lists as

elements. For example, consider the list '((a) b (c d) e). This

list contains four components, so, at the top level, we will need four

rectangles, just as in the previous example for the list '(d c b

a). Here, however, the first component designates the list '(a), which

itself involves the box-and-pointer diagram already discussed. Similarly,

the list '(c d) has two boxes for its two components (as in the diagram

for '(b a) above). The resulting diagram is:

Throughout these diagrams, the empty list is represented by a null

pointer, a diagonal line. Thus, the list containing the empty list,

(()) – that is, the value of the expression (cons null null) –

is represented by a rectangle with lines through both halves:

Pairs that are not lists

While we consistently have discussed cons in the context of lists,

Scheme allows cons to be applied even when the second argument is not

a list. For example, (cons 'a 'b) is a legal expression; its value

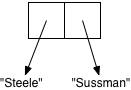

is represented by the following box-and-pointer diagram:

You may have noticed that some of your lists ended with a dot before the last character. In fact, whenever Scheme is asked to print out a sequence of linked pairs that don’t end with null, it uses dot notation, as in (a . b). Here, the dot indicates that cons has been applied, but the second argument is not a list. Similarly, the value of (cons 1 'a) is the pair (1 . a), and the value of (cons "Steele" "Sussman") is ("Steele" . "Sussman"). Using a box-and-pointer representation, this last result would be drawn as follows:

The car and cdr procedures can be used to recover the halves of one

of these improper lists:

> (car (cons 'a 'b))

'a

> (cdr (cons 'a 'b))

'b

Note that the cdr of such a structure is not a list.

When Scheme tries to print out a pair structure, it uses what we might call an optimistic assumption. If the next thing is null or a pair, it assumes that it’s a list, and therefore uses a space before the next object. When it hits the end and finds no null, it inserts the dot there, but not earlier.

A pair predicate

The pair? predicate returns #t when it is given any structure that is printed as a dotted pair, or indeed any structure that cons can return as its value. (Basically, pair? determines whether the object it is given is one of those two-box rectangles.)

Recursion with pairs

Just as lists can be nested within lists, so pairs can be nested within pairs, as deeply as you like. For instance, here is a pair structure that contains the first eight natural numbers:

To build this structure in Scheme, we can use repeated calls to cons, thus:

(cons (cons (cons 0 1)

(cons 2 3))

(cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7)))

or we can use the dotted-pair notation inside a literal constant beginning with a quote:

'(((0 . 1) . (2 . 3)) . ((4 . 5) . (6 . 7)))

or

'(((0 . 1) 2 . 3) (4 . 5) 6 . 7)

(As we’ve said previously, we’d prefer that you use cons rather than

quote to build structures.)

If we have a pair structure that is constructed by repeated invocations of

cons, starting from constituents of some simple type such as numbers

or strings, we call such a structure a tree. (We often prefix the

word tree with the type from which the tree is built, such as number

tree; alternately we suffix the word tree with of and then the type,

as in tree of numbers.) We will look at trees in some more depth in the

reading on deep recursion. For now, let’s consider a basic approach.

In particular, when we are dealing with a tree, we can use pair

recursion, which adapts the shape of the computation to the shape of

the particular pair structure on which we operate. In pair recursion,

the base cases are the non-pair values, those that must therefore

be operated on directly. For the non-base cases – those that are pairs

– we invoke the procedure recursively twice (once for the car, once

for the cdr) and combine the values of the recursive calls to get the

final result of the operation.

For instance, here is how we’d find the sum of the numbers in a pair structure like the one diagrammed above.

;;; (sum-of-number-tree ntree) -> integer?

;;; ntree : treeof number?

;;; Sums all the numbers in a number tree.

(define sum-of-number-tree

(lambda (ntree)

(if (pair? ntree)

(+ (sum-of-number-tree (car ntree))

(sum-of-number-tree (cdr ntree)))

ntree)))

> (sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons (cons 0 1)

(cons 2 3))

(cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

28

When this procedure is applied to a base case – that is, just a number rather than a collection of numbers fitted into a pair structure – it returns the number unchanged:

> (sum-of-number-tree 19)

19

There is no such thing as an empty pair analogous to an empty list. Every

pair has exactly two components, and it is always valid to take the car

and the cdr of a pair. So the base case for a pair recursion is just

any value that is not itself a pair.

You can find a full trace of the more complicated sum at the end of this reading.

Why pay attention to pairs

You may be wondering why we pay so much attention to these pair things. (You’ll probably be wondering why we ask you to pay so much attention after doing the lab). There are a few reasons. First, we find that students better understand lists (and related structures) if they have an understanding of what’s going on behind the scenes. Second, there are many instances in which we are better off building trees (like those above) than lists. Third, pair structures provide an additional mechanism for thinking about recursion.

The pair structures also reveal a bit about Scheme terminology. In the

first computers on which LISP (the forerunner of Scheme) was implemented,

there was an underlying memory structure that had two cells, which made

it a convenient way to implement pairs. On that computer, the operations

used to remove values from the structure were car (shorthand for

“contents of address register”) and cdr (shorthand for “contents

of decrement register”, even though some people mistakenly claim it

stands for “contents of data register”).

Abbreviated pair procedures

Once you start working with more complex pair structures, you will find yourself writing things like

(car (car (cdr (cdr thing))))

For readability and concision, most implementations of Scheme provide shorthands for nested calls to car and cdr.

For example, (cadr x) is a shorthand for (car (cdr x)) (that is, element 1 of the list), (caddr) is a shorthand for (car (cdr (cdr x))) (that is, element 2 of the list), (caar list) is a shorthand for (car (car list)), and (caaddr thing)` is a shorthand for the long expression from the start of this section.

Some of us try to think of the d’s as representing “drop” and the a’s as representing “access first”.

And, as in the case of composition, we read from right to left.

For example, caddr means “drop two elements and then take the first remaining element.

Why would you want two car operations in a row? For lists, it might be that you are working with a list of lists.

Some of us find it easiest to think of the compound procedures as taking the nested calls and “squishing them together”, eliminating the intervening r’s and c’s.

The pronunciation of these procedures varies. Some refer to cadr as “cad-er”.

Some refer to “cddr” as “cuh-did-er”.

Some, presumably from the Boston area, refer to caar as caaaah, with a drawn-out “a”.

Most often, people pronounce these operations by reading the letters, pronouncing caddr as “see eh dee dee are”. Fortunately, all of these letters require only one syllable.

In any case, you will quickly find it easier to read (and write) these shorthands than it is to read (and write) the nested calls.

Self checks

Check 1: Pair structure processing (‡)

The way we have drawn pair structures above makes it easy to think about

car and cdr operation. Reading from the inside out, you simply

follow the arrow from the left side of the pair for car or the arrow

from the right side of the pair for cdr.

a. Using this strategy, find the values corresponding to the following commands applied to the structure repeated below.

caarcadrcaaddr

b. Using an analog of the visual strategy, what sequence of commands

would you need to extract the 'e and 'd, respectively?

Check 2: Pair recursion

a. How does the base case test for pair recursion differ from the base case test for other types of recursion you have seen?

b. Why are there two calls to sum-of-number-tree in its recursive case?

Tracing sum-of-number-tree

Just in case you weren’t sure how sum-of-number-tree works, we’ll

explore a trace of the example.

Here’s the procedure again.

(define sum-of-number-tree

(lambda (ntree)

(if (pair? ntree)

(+ (sum-of-number-tree (car ntree))

(sum-of-number-tree (cdr ntree)))

ntree)))

And here’s the exprssion we promised to trace.

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons (cons 0 1)

(cons 2 3))

(cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; We have a pair, so we use the consequent

--> (+ (sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 0 1)

(cons 2 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Evaluating the first recursive call. Once again, we have a pair

--> (+ (+ (sum-of-number-tree (cons 0 1))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 2 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Evaluating the innermost recursive call. Still using the pair case.

--> (+ (+ (+ (sum-of-number-tree 0)

(sum-of-number-tree 1))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 2 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Evaluating the innermost recursive call. Finally, a base case!

--> (+ (+ (+ 0

(sum-of-number-tree 1))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 2 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Evaluating the innermost recursive call. Another a base case.

--> (+ (+ (+ 0

1)

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 2 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Something easy: Add two numbers

--> (+ (+ 1

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 2 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Back to a recursive call. Pair case.

--> (+ (+ 1

(+ (sum-of-number-tree 2)

(sum-of-number-tree 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; The innermost recursive call is the base case

--> (+ (+ 1

(+ 2

(sum-of-number-tree 3)))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; The innermost recursive call is the base case

--> (+ (+ 1

(+ 2

3))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; Addition!

--> (+ (+ 1

5)

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; More addition!

--> (+ 6

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

; We've completed the first subtree. Now we need to handle the

; recursion on the second subtree. Once again, we have the pair case.

--> (+ 6

(+ (sum-of-number-tree (cons 4 5))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 6 7))))

; Recurse on the innermost subtree. Another pair case.

--> (+ 6

(+ (+ (sum-of-number-tree 4)

(sum-of-number-tree 5))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 6 7))))

; A base case.

--> (+ 6

(+ (+ 4

(sum-of-number-tree 5))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 6 7))))

; Another base case.

--> (+ 6

(+ (+ 4

5)

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 6 7))))

; Addition

--> (+ 6

(+ 9

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 6 7))))

; We're getting close. But we still have another pair case.

--> (+ 6

(+ 9

(+ (sum-of-number-tree 6)

(sum-of-number-tree 7))))

; A base case.

--> (+ 6

(+ 9

(+ 6

(sum-of-number-tree 7))))

; Our last base case (I hope).

--> (+ 6

(+ 9

(+ 6

7)))

; Addition

--> (+ 6

(+ 9

13))

; Addition

--> (+ 6

22)

; Addition

--> 28

Wasn’t that fun?

If we’re willing to do operations in parallel, it’s a bit simpler.

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons (cons 0 1)

(cons 2 3))

(cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

--> (+ (sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 0 1))

(cons 2 3))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons (cons 4 5)

(cons 6 7))))

--> (+ (+ (sum-of-number-tree (cons 0 1))

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 2 3)))

(+ (sum-of-number-tree (cons 4 5)

(sum-of-number-tree (cons 6 7))))

--> (+ (+ (+ (sum-of-number-tree 0)

(sum-of-number-tree 1))

(+ (sum-of-number-tree 2)

(sum-of-number-tree 3)))

(+ (+ (sum-of-number-tree 4)

(sum-of-number-tree 5))

(+ (sum-of-number-tree 6)

(sum-of-number-tree 7))))

--> (+ (+ (+ 0

1)

(+ 2

3))

(+ (+ 4

5)

(+ 6

7)))

--> (+ (+ 1

5)

(+ 9

13))

--> (+ 6

22)

--> 28

Perhaps a bit easier to follow, even without the narration.