Transforming lists

- Summary

- We investigate a particular form of decomposition relevant in computing in which transformations over a collection of values are really transformations of the individual elements of the collection.

- Prerequisites

- List Basics.

Imagine representing your five favorite colors as a list. That’s fairly straightforward.

> (define faves

(list (rgb 128 0 128) (rgb 255 0 255) (rgb 255 0 128)

(rgb 128 0 255) (rgb 192 0 192)))

Now, imagine deciding that you want to make all of them slightly darker. As we’ve done when working with images, we can decompose this into the simpler problem of making one color darker. Here’s one possibility.

;;; (rgb-darker c) -> color?

;;; c : color?

;;; Create a slightly darker version of c.

(define rgb-darker

(lambda (c)

(rgb (- (rgb-red c) 32)

(- (rgb-green c) 32)

(- (rgb-blue c) 32))))

We can now make any color darker. However, how do we do this for a collection of colors, a collection we’ve represented as a list?

Note that the calculation of each new color is independent of the other colors. That is, one adjusted color depends only on the color and not the other colors. In this situation, we want to apply our solution for a single color to every element of the list.

We can do so manually.

> (define darker-faves

(list (rgb-darker (rgb 128 0 128)) (rgb-darker (rgb 255 0 255))

(rgb-darker (rgb 255 0 128)) (rgb-darker (rgb 128 0 255))

(rgb-darker (rgb 192 0 192))))

However, it’s a lot of work to type rgb-darker that many times. What if we had dozens of colors in our list? Would we really want to keep typing rgb-darker? And what are the odds that we’d make a mistake with parentheses somewhere along the way? There must be a better option.

In Scheme, we realize the behavior of lifting a function to a list of values with the map function:

> (define darker-faves (map rgb-darker faves))

> (map rgb->string darker-faves)

'("96/0/96" "223/0/223" "223/0/96" "96/0/223" "160/0/160")

Note that the map procedure does not affect the original list.

> (map rgb->string faves)

'("128/0/128" "255/0/255" "255/0/128" "128/0/255" "192/0/192")

The map procedure

map is a powerful procedure! It allows to concisely describe how to transform the values of a list in terms of an operation over a single element of the list. Let’s break down how you use map.

map itself is a function of two arguments as seen in our above example. (There are other ways to call map. For now, we’ll treat it as a function of two arguments.)

-

The first argument is a function that transforms a single element of the list. By “transform”, we mean the function:

- Takes as an input an element of the list.

- Produces as an output the result of transforming that element.

In our above example,

rgb-darkeris a function that transforms an color into a new, adjusted color. -

The second argument is a list that contains the elements that we wish to transform.

Any transformation over colors can be passed to our call to map with faves. For example, perhaps we want to set the red component of each color to 255.

> (define maximize-red

(lambda (c)

(rgb 255

(rgb-green c)

(rgb-blue c))))

> (map rgb->string (map maximize-red faves))

'("255/0/128" "255/0/255" "255/0/128" "255/0/255" "255/0/192")

We might also check how many of the colors are bright.

;;; (rgb-brightness c) -> real? (between 0 and 100)

;;; c : color?

;;; Find the approximate perceived brightness of c

(define rgb-brightness

(lambda (c)

(round (* 100/255

(+ (* .30 (rgb-red c))

(* .59 (rgb-green c))

(* .11 (rgb-blue c)))))))

;;; (rgb-bright? c) -> boolean?

;;; c : color?

;;; Determine if c is "bright" (with a perceived brightness of at

;;; least 50).

(define rgb-bright?

(lambda (c)

(>= (rgb-brightness c) 50)))

> (map rgb-bright? faves)

'(#f #f #f #f #f)

None of our favorite colors. Given how much green contributes to brightness, I suppose that makes sense.

Transforming collections of data with map.

This last example alludes to the idea that map isn’t constrained to keep the type of the elements of the resulting list the same as the old list. Indeed, the power of the map is we can transform the list in arbitrary ways as long as those transformations are independent between list elements. As long as we can recognize the “collection” being transformed in our problem, we can write solutions in surprisingly elegant ways.

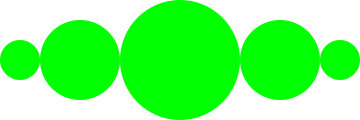

As an example, consider the problem of drawing the following image:

Using decomposition, we might recognize this image as a bunch of green circles of different sizes. We could write a function that captures a single green circle parameterized by size:

(define green-circle

(lambda (radius)

(solid-circle radius "green")))

And we can use green-circle to better capture the structure of the image in code:

> (beside (green-circle 20)

(green-circle 40)

(green-circle 60)

(green-circle 40)

(green-circle 20))

But look at that redundancy! Calling green-circle many times is undesirable: it takes time and effort to read and write the code. Furthermore, the “repetitive” nature of the image isn’t truly captured in the code. This keeps us from generalizing the function further, e.g., varying the numbers of green-circles in the figure.

However, if we instead decompose the problem as a transformation over lists instead, we’ll arrive at a better solution. But where is the list in this code? While there isn’t a list anywhere in the code for us to immediately map over, we do note that the image can be thought of as a collection of circles.

With this in mind, we can decompose the problem of generating a collection of circles into creating a single circle. The way we do this is with green-circle, passing in its size. The size is therefore the element we are transforming!

We’re transforming a size into a circle by way of the green-circle function.

We can then transform a collection of sizes into a collection of circles by lifting green-circle using map:

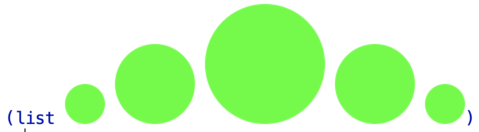

> (define circles (map green-circle (list 20 40 60 40 20)))

> circles

(Note: We can’t easily reproduce the layout of the images inlined with the text in HTML, so the output from the last map call is a screenshot of the output on one of the instructor’s computers.)

Another way to work with lists of values

We aren’t done yet! This isn’t a single image composed of a bunch of green circles. This is a list of green circles of different sizes (note the (list ... ) surrounding the circles).

As with the original version of the code, we need to use beside to combine the circles. However, if we simply pass this expression to beside, we get an error:

> (beside circles)

.../lang/prim.rkt:24:44: beside: arity mismatch;

the expected number of arguments does not match the given number

expected: at least 2

given: 1

arguments...:

Why does this error occur? Let’s think carefully about the types of the values involved:

besideis a function that takes a collection of images, one per argument, e.g.,(beside image1 image2 image3 image4 image5). Each argument is a single image.circlesis defined to be(map green-circle (list 20 40 60 40 20))which is a list of images.

Finally, consider the complete expression (besides circles). Each argument to besides should be a single image but circles is a list of images instead. That’s where our error arises!

Ultimately, we have to someone pass in each image in the list circles to each argument position of besides. How do we do this? It turns out we have to employ an additional standard Scheme library function, apply.

> (apply beside circles)

More generally, apply is a helpful standard library function when working with lists of arguments.

apply takes two arguments:

- A function to run or apply on a collection of arguments.

- The collection of arguments to apply to the function, stored in a list.

As a simpler example of apply, consider the simple (+) function which can take any number of arguments:

> (+ 1 2 3 4 5)

15

While (+) takes any number of arguments, it cannot take a single list as an argument:

> (+ (list 1 2 3 4 5))

+: contract violation

expected: number?

given: '(1 2 3 4 5)

To pass this list of numbers to (+), we can use the apply function:

> (apply + (list 1 2 3 4 5))

15

Pause for reflection

So let’s summarize the image code we’ve written:

(define green-circle

(lambda (radius)

(solid-circle radius "green")))

(define circles

(map green-circle (list 20 40 60 40 20)))

(define circles-besides

(apply beside circles))

> circles-besides

We’ve decomposed the problem of drawing the circles not as a series of repeated calls to green-circles but as a collection that is the result of transforming the sizes of the circles into green circles. While this interpretation may have come less naturally to you, once you understand transformations with map this solution is more readable and more concise.

It’s also more flexible. Suppose we wanted to add two more circles of size 30 to the picture and change the middle one to size 50. That’s fairly straightforward.

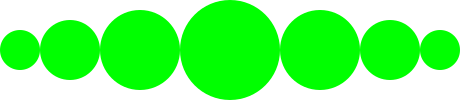

> (define seven-circles

(apply beside (map green-circle (list 20 30 40 50 40 30 20))))

> seven-circles

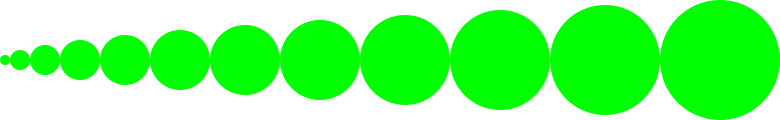

What if we wanted circles of sizes 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60? That seems like a lot of typing? But we can use map and range.

> (define times5

(lambda (val)

(* 5 val)))

> (define many-green-circles

(apply beside (map green-circle (map times5 (range 1 13)))))

> many-green-circles

This is the power of decomposition (and lists) in action! In particular, if we use appropriate abstractions, we can create highly reusable code that both captures our intent but can be used in other contexts with minimal modification.

Detour: Rethinking many-green-circles with cut and composition

Let’s reconsider what we’ve just written.

> (define green-circle

(lambda (radius)

(solid-circle radius "green")))

> (define times5

(lambda (val)

(* 5 val)))

> (define many-green-circles

(apply beside (map green-circle (map times5 (range 1 13)))))

If you’ve learned how to cut procedures, you know we could write something even more concise. In particular, we could get rid of the definition of times5 and then replace its use by a cut expression.

> (define many-green-circles

(apply beside (map green-circle (map (cut (* 5 <>)) (range 1 13))))))

We could even do the same with the green-circle part.

> (define many-green-circles

(apply beside

(map (cut (solid-circle <> "green"))

(map (cut (* 5 <>))

(range 1 13)))))

And if we use function composition, we can even avoid calling map twice.

> (define many-green-circles

(apply beside

(map (o (cut (solid-circle <> "green"))

(cut (* 5 <>)))

(range 1 13))))

Is this still decomposed? Yes! We’ve broken up the problem into parts; we’ve just avoided naming the individual parts.

Thinking with types

As you’ve likely discovered already, it is important that we use the correct types when we run our procedures. With both map and apply, we have to think a bit more deeply about types.

What are the types of the inputs to map?

That’s a real question. Take a minute and think about it.

We mean it.

Hopefully, you said something like

maptakes two inputs. The first is a procedure. The second is a list of values.

But there’s more to it than that. There’s a relationship between the procedure and the list of values. In particular, the procedure much be applicable to each value in the list. Let’s consider two simple examples.

You may remember that sqr computes the square of a number and string-upcase converts a string to upper case.

> (sqr 5)

25

> (string-upcase "quiet")

"QUIET"

If we’re using map, we should use sqr with lists of numbers and string-upcase with lists of strings.

> (range 2 6)

'(2 3 4 5)

> (map sqr (range 2 6))

'(4 9 16 25)

> (string-split "please be quiet not loud" " ")

'("please" "be" "quiet" "not" "loud")

> (map string-upcase (string-split "please be quiet not loud" " "))

'("PLEASE" "BE" "QUIET" "NOT" "LOUD")

But what happens if we don’t match types? Let’s see.

> (map sqr (string-split "please be quite not loud" " "))

. . sqr: contract violation

expected: number?

given: "please"

> (map string-upcase (range 2 6))

. . string-upcase: contract violation

expected: string?

given: 2

You’ll note that we get errors. Are they the errors you expected? It might be nicer if DrRacket more explicitly told us that the elements of the list were not the correct types for the procedure. But it’s done that in its own way.

What if we do something even stranger, such as writing something other than a procedure in the procedure position, or something other than a list in the list position? Let’s try.

> (map 5 (list 1 2 3))

. . map: contract violation

expected: procedure?

given: 5

> (map sqr 5)

. . map: contract violation

expected: list?

given: 5

It’s good to see that these error messages are clear. Let’s do our best to remember those so that when we see them, we know what’s gone wrong.

Next, let’s move on to apply. Like map, apply takes a procedure and a list as parameters. While map applies the procedure element by element, apply applies the procedure to the elements en masse, as it were.

> (apply * (list 2 3 4))

24

> (apply string-append (list "this" "and" "that"))

"thisandthat"

Once again, we should see what happens if we give incorrect types.

> (apply * (list 2 3 4))

24

> (apply string-append (list "this" "and" "that"))

"thisandthat"

> (apply * (list "this" "and" "that"))

. . *: contract violation

expected: number?

given: "this"

argument position: 1st

other arguments...:

> (apply * (list 2 3 "four"))

. . *: contract violation

expected: number?

given: "four"

argument position: 3rd

other arguments...:

> (apply string-append (list 2 3 4))

. . string-append: contract violation

expected: string?

given: 2

argument position: 1st

other arguments...:

> (apply 2 (list 2 3 4))

. . application: not a procedure;

expected a procedure that can be applied to arguments

given: 2

arguments...:

> (apply 2 3)

. . apply: contract violation

expected: procedure?

given: 2

argument position: 1st

other arguments...:

> (apply + 2 3 4)

. . apply: contract violation

expected: list?

given: 4

argument position: 4th

other arguments...:

We will need to practice reading error messages like those. But each is saying, in essence, “you got the types wrong”. When you get such error messages, reflect on what type issues you might have.

Extending map

We’ve explored map with one-parameter procedures and a single list. But map can also use multi-parameter procedures and multiple lists. In that case, it takes corresponding elements of each list. Let’s explore a quick example, which we may return to in the lab.

> (define sized-circle

(lambda (radius)

(solid-circle radius "blue")))

> (range 10 30 5)

'(10 15 20 25)

> (map sized-circle (range 10 30 5))

; Output left to reader's imagination or experimentation

> (define shaded-circle

(lambda (shade)

(solid-circle 20 (rgb 0 0 255 shade))))

> (range 50 251 50)

'(50 100 150 200 250)

> (map shaded-circle (range 50 251 50))

; Output to left reader's imagination or experimentation

> (define blue-circle

(lambda (radius shade)

(solid-circle radius (rgb 0 0 255 shade))))

> (map blue-circle (range 10 31 5) (range 50 251 50))

; Output to left reader's imagination or experimentation

And, as we’ve just seen, it’s probably worth looking at some different kinds of errors.

> (map blue-circle (list 10 20) (list 50 100 150))

. . map: all lists must have same size

first list length: 2

other list length: 3

procedure: #<procedure:blue-circle>

> (map blue-circle (list 10 20))

. . map: argument mismatch;

the given procedure's expected number of arguments does not match the given number of lists

given procedure: blue-circle

expected: 2

given: 1

argument lists...:

'(10 20)

> (map blue-circle (list 10 20 30) (list 50 30 "pink"))

. . .../lang/prim.rkt:24:44: circle: expects a mode as second argument, given "pink"

Yeah, that last one isn’t all that helpful.

Mental models: Tracing map and apply

As we’ve seen, it’s useful to be able to trace our Racket code by hand to consider what the Racket evaluator is doing (or at least what we think it’s doing) and, therefore, why we get the results or errors that we do. And you already know many aspects of the mental model for doing so, particularly the rule that you evaluate arguments before applying a procedure and that you use substitution for user-defined procedures.

For map, we use the rule “Replace (map PROC (list VAL0 VAL1 ...)) with (list (PROC VAL0) (PROC VAL1) ...).” (There’s a similar rule for the multi-parameter map.

For apply, we use the rule “Replace (apply PROC (list VAL0 VAL1 ...)) with (PROC VAL0 VAL1 ...).

So let’s try an example.

(define dub

(lambda (x)

(* 2 x)))

; (apply + (map dub (range 3 8 2)))

; --> (apply + (map dub (list 3 5 7)))

; --> (apply + (list (dub 3) (dub 5) (dub 7)))

; --> (apply + (list (* 2 3) (dub 5) (dub 7)))

; --> (apply + (list 6 (dub 5) (dub 7)))

; --> (apply + (list 6 (* 2 5) (dub 7)))

; --> (apply + (list 6 10 (dub 7)))

; --> (apply + (list 6 10 (* 2 7)))

; --> (apply + (list 6 10 14))

; --> (+ 6 10 14)

; --> 30

Note that when we’re working with lists, it’s helpful to explicitly write (list ...), which reminds us that we’re dealing with a list and not an expression to further evaluate.

Here’s an example with the multi-list map.

; (apply * (map - (list 5 10 15) (list 2 3 4)))

; --> (apply * (list (- 5 2) (- 10 3) (- 15 4)))

; --> (apply * (list 3 (- 10 3) (- 15 4)))

; --> (apply * (list 3 7 (- 15 4)))

; --> (apply * (list 3 7 11))

; --> (* 3 7 11)

; --> (* 3 7 11)

; --> 231

While we’ll rarely write out all of these steps, it helps to keep them in mind as we think about what map and apply are doing. And we will, on occasion, pull out a piece of paper, a whiteboard, or an electronic document to think through part of the

steps of an evaluation.

Self-checks

Self-check 1 (Differences)

Write a function decrement that takes an integer as input and returns an integer one less than the input.

Now use decrement and map to write an expression that decrements the contents of the following list three times:

(define example-list (list 10 20 30 40 50))

Self-check 2 (Colorful circles) (‡)

Here’s a function, (thickly-outlined-circle color), that makes a circle of diameter 20 of the appropriate color with a thick black outline.

;;; (thickly-outlined-circle color) -> image?

;;; color : color?

;;; Make a thickly outlined circle of the specified color.

(define thickly-outlined-circle

(lambda (color)

(overlay (outlined-circle 20 "black" 5)

(solid-circle 20 color))))

Here’s the rgb-darker function we used above.

;;; (rgb-darker c) -> color?

;;; c : rgb?

;;; Create a slightly darker version of c.

(define rgb-darker

(lambda (c)

(rgb (- (rgb-red c) 32)

(- (rgb-green c) 32)

(- (rgb-blue c) 32))))

a. Using apply and map, make a picture of seven outlined circles in the rainbow colors ("red", "orange", "yellow", "green", "blue", "indigo", and violet) in a row.

b. Using apply and map, make a picture of seven outlined circles in darker versions of the rainbow colors (using two calls to rgb-darker). Note that you’ll need to convert the color names to RGB colors with color-name->rgb and then make them darker with two calls to rgb-darker.

Note: You might need three or four calls to map (or a particularly good composition of functions).